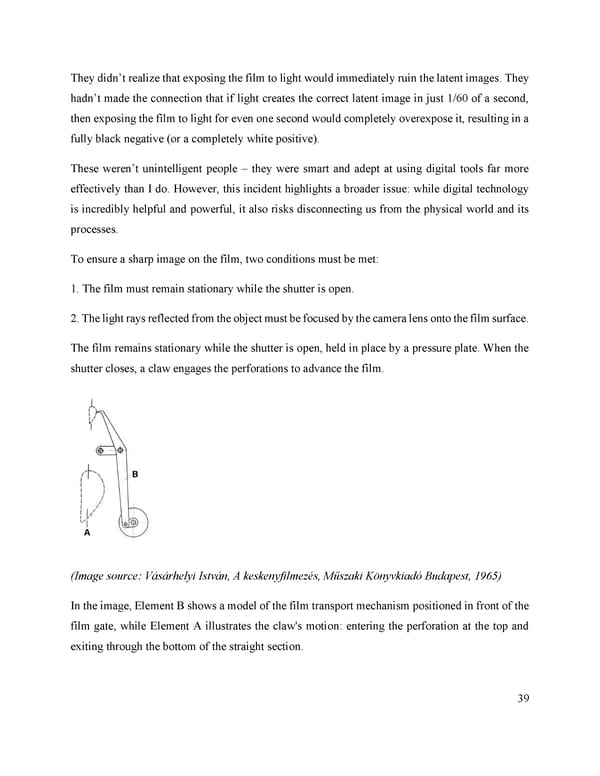

They didn’t realize that exposing the film to light would immediately ruin the latent images. They hadn’t made the connection that if light creates the correct latent image in just 1/60 of a second, then exposing the film to light for even one second would completely overexpose it, resulting in a fully black negative (or a completely white positive). These weren’t unintelligent people – they were smart and adept at using digital tools far more effectively than I do. However, this incident highlights a broader issue: while digital technology is incredibly helpful and powerful, it also risks disconnecting us from the physical world and its processes. To ensure a sharp image on the film, two conditions must be met: 1. The film must remain stationary while the shutter is open. 2. The light rays reflected from the object must be focused by the camera lens onto the film surface. The film remains stationary while the shutter is open, held in place by a pressure plate. When the shutter closes, a claw engages the perforations to advance the film. (Image source: Vásárhelyi István, A keskenyfilmezés, Műszaki Könyvkiadó Budapest, 1965) In the image, Element B shows a model of the film transport mechanism positioned in front of the film gate, while Element A illustrates the claw's motion: entering the perforation at the top and exiting through the bottom of the straight section. 39

Lost Analogue: Exploring Film, Music, and Interdisciplinary Methods in Education Page 39 Page 41

Lost Analogue: Exploring Film, Music, and Interdisciplinary Methods in Education Page 39 Page 41