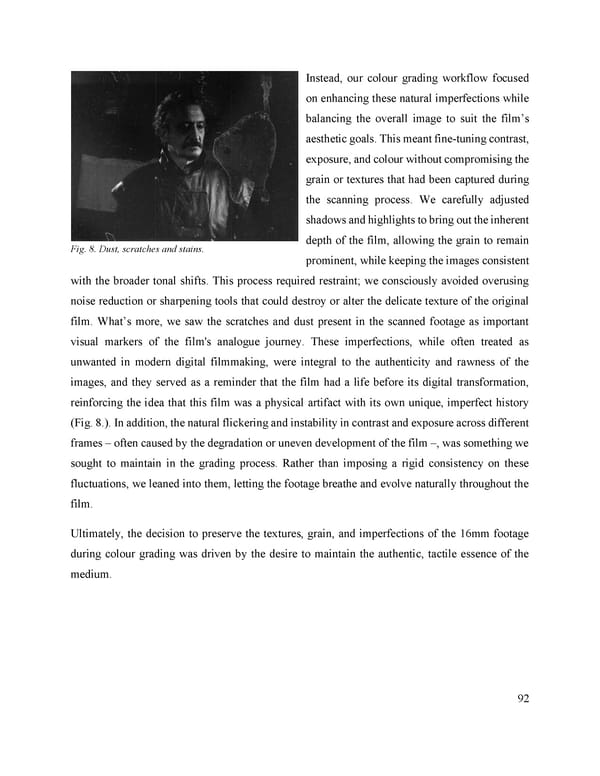

Instead, our colour grading workflow focused on enhancing these natural imperfections while balancing the overall image to suit the film’s aesthetic goals. This meant fine-tuning contrast, exposure, and colour without compromising the grain or textures that had been captured during the scanning process. We carefully adjusted shadows and highlights to bring out the inherent depth of the film, allowing the grain to remain Fig. 8. Dust, scratches and stains. prominent, while keeping the images consistent with the broader tonal shifts. This process required restraint; we consciously avoided overusing noise reduction or sharpening tools that could destroy or alter the delicate texture of the original film. What’s more, we saw the scratches and dust present in the scanned footage as important visual markers of the film's analogue journey. These imperfections, while often treated as unwanted in modern digital filmmaking, were integral to the authenticity and rawness of the images, and they served as a reminder that the film had a life before its digital transformation, reinforcing the idea that this film was a physical artifact with its own unique, imperfect history (Fig. 8.). In addition, the natural flickering and instability in contrast and exposure across different frames – often caused by the degradation or uneven development of the film –, was something we sought to maintain in the grading process. Rather than imposing a rigid consistency on these fluctuations, we leaned into them, letting the footage breathe and evolve naturally throughout the film. Ultimately, the decision to preserve the textures, grain, and imperfections of the 16mm footage during colour grading was driven by the desire to maintain the authentic, tactile essence of the medium. 92

Lost Analogue: Exploring Film, Music, and Interdisciplinary Methods in Education Page 92 Page 94

Lost Analogue: Exploring Film, Music, and Interdisciplinary Methods in Education Page 92 Page 94